Specific physical training programme at SIA Academy

At Soccer Inter-Action we apply a new high performance functional specific physical training programme based on physical qualities (strength, flexibility, endurance, speed…) with the objective of improving the physical capacity of the student in the sport of football, as well as in other sports to strengthen the musculature most prone to injuries in this sport.

All the work is developed in a dynamic and simple way with specific material, the intensity and effort is set by you.

What is “specific physical preparation”?

This is the part of training that aims to get the athlete in the best possible shape, using their natural aptitudes and developing their physical qualities to the maximum, by means of systematic, gradual and progressive exercises that enable the body to adapt to the specific and technical training of each sport and thus obtain optimum sporting performance. Specific and individualised physical preparation focused on overcoming all types of tests.

Sport is a very important social phenomenon nowadays. What began with the epic, ends with the multidisciplinary study, the scientific methodology, the overall vision and the global assessment of sport as fundamental items to improve sporting performance. Nowadays, the number of sportsmen and sportswomen is an indicator of the quality of life of society divided into different ages without any restriction.

There is no sport that does not need physical preparation, as an important basis, to obtain maximum performance and it would be unthinkable that an athlete could obtain good results only by training the technical part of his or her sport.

It is clear that some sports require more physical work than others, for example, nobody would think that a top level football, rugby or basketball player does not need a physical preparation programme, also the combination of cardiovascular work with muscular work is basic to be able to perform at the highest level in competitions.

At Soccer Inter-Action we believe that sports preparation or individualised training is recommended for all ages between all stages of sports initiation as long as the workloads and volumes are individualised and specific. Not only age is important, but also biological maturation, although there should always be individualised and personalised training according to age and gender. Training should be multilateral, as young people can withstand higher volumes of training than high intensities, and it should always be borne in mind that they need more time to recover and never enter a fatigue phase at an early age.

Each athlete has different characteristics, hence the importance of an individualised training plan, as each athlete has a different capacity for adaptation due to the SN, in some the sympathetic predominates and in others the parasympathetic, which is why we should never group athletes together in the same work, due to their differences:

-Anthropometric -Functional

-Phenotype -Motor

-Psychological -Motivation

-Adaptation -Genotype

-Physical condition level

A Training Plan in our High Performance Centre would have the following five points to develop qualities such as skill, balance, speed, flexibility, coordination, explosive strength, etc;

- Preparatory Period:

- General Conditioning:

- Specific Preparatory:

- Competitive Period:

- Transition Period:

To be transferred and applied to the techniques and tactics specific to the sport practised, with greater efficiency.

By now we should be clear on “What is Specific Fitness Training“.

Principle of exercise training that refers to the fact that the training of muscles is a sport specific way of not conditioning the body for different sports or exercises; e.g. a marathon runner trains for distance running, but may not have the ability to do intense weight lifting; in this we use the principle of specific adaptations to imposed demands. Then Specific Physical Training aims to increase endurance, strength, power and flexibility by training the muscles that are used specifically in a particular sport using the sport’s own equipment.

We use specific or special exercises for this purpose.

Exercises identical to the movement performed in competitive situations, but with different load demands and as partial exercises or movements, similar to the competitive movement or at least activating the same muscle groups as the competitive action. We focus on the fact that specific exercises should mimic the movement pattern of the competition as closely as possible. That “the structure, intensity and duration of which approximately reproduce the competitive movements”.

The objective of specific exercises is and must be the development of basic physical capacities (strength, endurance, speed, flexibility) but also the development and improvement of technique, tactics and even psychological qualities that may be decisive for performance (e.g. capacity for suffering, control of emotions).

They make it possible to modify the condition of the athlete through specific means (specific materials, specific context). However, there are those who differentiate between two groups of specific exercises according to their main objective:

– Exercises of a conditioning or physical nature.

– Learning exercises.

Specific physical exercises can pursue different objectives such as:

– The improvement of conditional capacities.

– The learning and consolidation of technical-sporting actions of the modality.

– The improvement of technical-tactical skills.

What are the 5 Benefits of Individualised Specific Physical Training for High Performance?

1st Benefit: Multidisciplinary work

Whenever we talk about sports performance, we should not only think about the training itself, since, from a sporting perspective, all areas must be interconnected, through multidisciplinary work, as we have seen in (the Soccer Inter-Action and FC Porto Dragon Force Valencia facilities) through the medical, nutritional, physiotherapeutic, sports preparation and functional injury prevention-recovery areas).

To be able to always know, apply and adapt the general principles of physical sports training to different contexts (health, initiation, education and sports performance). All individualised work must be supervised by university graduates with experience in sport. The determinants of performance in football are based on energy systems, stabilisation and strength, technique and agility, mental preparation,

tactical preparation, rest and regeneration. It is necessary to differentiate and know the different pedagogical and biological principles that are the basis of training.

Knowing the usefulness of the application of the different principles of training in the different phases of adaptation: initial phases of adaptation, consolidation of adaptation and orientation of adaptation. Within the training we must know the initial planning, which changes in the different stages due to different extrinsic-intrinsic factors.

The principles of sport training are general rules drawn from sport sciences, and especially from pedagogy, psychology and sport biology. They should be interpreted as guiding principles and not as dogmas to be applied in all cases and applications (Gonzalez 1985).

General pedagogical principles

→ Conscious or active participation

→ Individualisation

→ Accessibility

Specific biological principles

→Functional unity

→Principle of overload

→Recovery

→ Reversibility

Specific methodological principles

→Multilaterality -Specificity

→Transfer -Variety

→Evaluation

Principles of temporal organisation

→Periodisation

→Repetition and continuity

→Progression

→Periodic regeneration

2nd Benefit: Planning, Adaptation and Analysis of individualised training loads.

The main planning lies in the assessment of the state of health and the evaluation of the physical and psychological capacities of the athlete: Biometry, cardio-respiratory capacities, neuromuscular capacity and the psychological profile of the athlete.

In this way, the most common errors in the training process can be avoided;

Carelessness in the recovery phase, with inadequate rest periods.

Training that is too intense, not in accordance with the athlete’s capacity.

Too many competitions with high demands, without planning the loads and recovery.

Is there any knowledge of the variations of place, time or climate, in competitions and training, which causes individual variations in each athlete? It is obvious that in order to adapt the physical condition to the demands of competition (especially in professional sportsmen and women), large doses of training are needed.

However, it is also true that if the training dose is increased too much, the risk of injury increases significantly. So, where is the balance point? How much training to improve without putting the health of athletes at risk? This is perhaps one of the most exciting questions in the world of training and that is why the best way is through specific and individualised work.

A recent study (Hulin, Gabbett, Lawson, Caputi, & Sampson, 2015) conducted with rugby players has been published that could guide us in this question. The researchers defined acute load as the total distance run during a microcycle, and chronic load as the average acute load over the 4 preceding consecutive microcycles.

The acute load: chronic load ratio (Hulin, et al., 2015) is considered to be a good predictor of injury. A value higher than 1 in this ratio represents a higher acute load than chronic load and vice versa. Well, players with high values of chronic load were shown to be more resistant to injury with moderate values in the acute load: chronic load ratio, while the risk of injury in these players increased with very high values in the acute load: chronic load ratio.

Therefore, it is very interesting to monitor the aforementioned variables at different times to try to predict and subsequently minimise the risk of injury or overtraining.

3rd Benefit: Knowledge of the Physiological Effects of Training.

We must take into account all the negative parameters that can occur during training sessions and the effects that arise in order to minimise them.

Within the Principle of Overload, as training sessions and competition days go by, players accumulate fatigue. Training at moderate or high intensities with a fatigued body could bring it to the brink of injury.

Routine fatigue monitoring, whether by objective or subjective means (Twist & Highton, 2013), could again help to predict and minimise the risk of injury. For their simplicity and reliability, I recommend the daily use of subjective means such as different oral or visual wellbeing questionnaires. (McLean,Coutts,Kelly, McGuigan&Cormack, 2015)

To avoid reversibility and maintain adaptations, training has to be a continuous process. Interruptions in training decrease sporting performance, as do periods of inactivity, which should be kept to a minimum. Considering that isolated exercises or very distant training sessions do not have any effect on the performance.

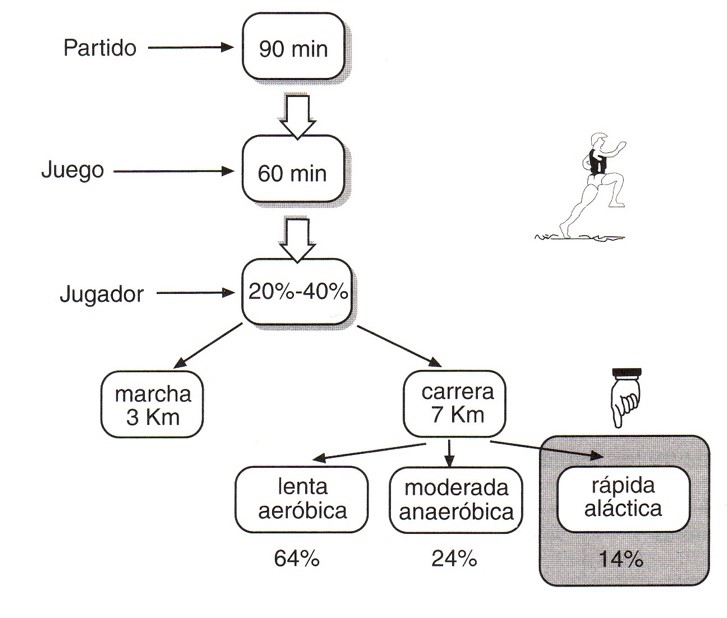

The distribution of effort in football is as follows:

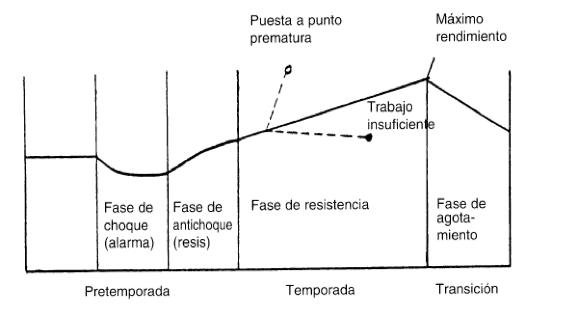

The load cannot be maintained throughout the year in the individual capacity limit zone. Therefore, the athlete cannot be in top form for a long time, nor can he/she maintain it uninterruptedly.

The load produces a maladjustment and during recovery, in response to the body’s reaction to this maladjustment, adaptation and supercompensation take place. This recovery requires a period of rest or a significant reduction in the load for all the regenerative and super-compensatory effects to take place.

It should be borne in mind that loading and recovery are always linked to a subsequent improvement in performance capacity. Repeated fatigue symptoms, produced by the load, raise the performance potential in the recovery phase and are a necessary prerequisite for performance enhancement.

All capacities are interrelated, the development of one will influence the level of the others (improve strength => loss of flexibility, improve endurance => loss of speed).

Our main objective with this method of individualised work on this problem is to find the balance between the capacities. To do this it is essential to know how they affect each other and how to interrelate them, avoiding phases of overtraining. All work must be progressive and personalised.

El carácter fásico de la adaptación requiere la subdivisión del año de entrenamiento en diferentes periodos. (tabla 2)

4th Benefit: Prevention – Recovery from sports injuries in an individualised way.

The great lie that is in our 21st century society where everything wants to be done as quickly as possible, the “everything” for everyone appears, and it is not like that at all, since each person is different and needs different stimuli to achieve their own individual sporting objectives, recovering different data we observe that all injuries do not have the same recovery time for different athletes, each athlete through their intrinsic factors has a very different stage recovery, which all injury protocols should be individualised for the specific athlete.

Muscle injuries are very common in sport, with an incidence ranging from 10% to 55% of all injuries (Garret, 1996; Beiner, 2001). Nowadays, there are few who doubt the importance that injury prevention has acquired in contemporary sport in general, and in football in particular.

In addition to the high economic cost of injury (up to 500,000 euros per month for a top European player) (Ekstrand, 2013), there is also a possible link between injury incidence and sporting performance (Eirale, Tol, Farooq, Smiley, & Chalbi, 2013; Hagglund et al., 2013).

These facts have led to an increase in research related to the subject, and a high concern and occupation of the members of the coaching staff to try to reduce the incidence of injury in their teams. Therefore, the first objective of any physical trainer when working with a football team (possibly the one that can have more impact on the work well done) should always be the prevention of injuries (Jarvis, 2015).

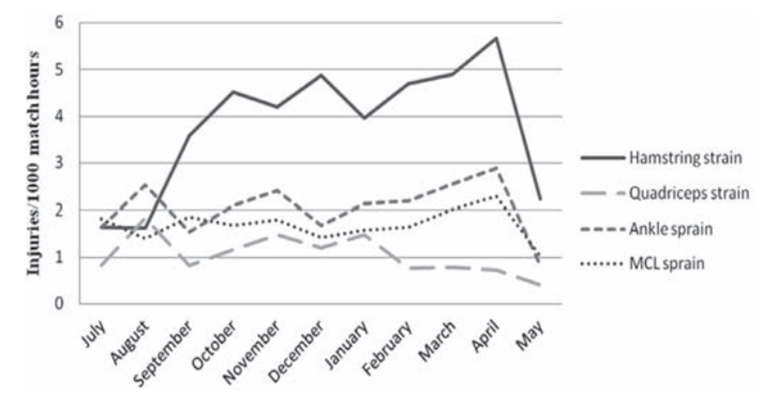

Injuries do not tend to occur evenly throughout the season (Ekstrand, Hagglund, & Walden, 2011) (Figure 1).

Injuries do not tend to occur evenly throughout the season (Ekstrand, Hagglund, & Walden, 2011).

The post-holiday period tends to be a period with a greatly increased incidence of injury, especially with regard to muscle injuries (Jarvis, 2015). It could be speculated as possible determinants of this increase in injuries, the accumulation of residual fatigue after the previous months of competition, the drop in temperatures, the playing fields (especially training) may be softer or more neglected (Jarvis, 2015).

It should always be taken into account that because only uninjured fibres or those that retain adequate glycolytic function work well, intense exercise requires the same effort for fewer fibres, increasing the likelihood of injury, so if the fibres take 48 h to recover and even more 72 h to replenish glycogen, here the reason for individualised recovery for each athlete, such as age and gender. (Olivé F, Borrell Pedrós J et al. Manual of sports injuries. Ed. Sport/Asepeyo 2013;1-189.)

Age and gender and their distribution in sports injuries is a much studied topic. Given that the number of injuries seen in male athletes, 2,595 (81 %), has been considerably higher than those seen in women, which were 607 (19 %). Between the ages of 15 and 25 years, the highest incidence of injury occurs in most sports. In a review of 3,202 injuries (Moreno 2002), the average age was 19.5 years, with extremes of 8 and 70 years; however, the age at which most injuries occurred was 17 years.

According to the incidence of injuries in Spain in the 2016-2017 survey, the most injured sports or activities are:

| 1º | Rhythmic gymnastics | 35% |

| 2º | Football | 27,5% |

| 3º | Swimming | 22,4% |

| 4º | Cycling | 19,4% |

| 5º | Running | 12,9% |

| 6º | Basketball | 7,7% |

| 7º | Tennis-Paddle | 6,5% |

| 8º | Athletism | 6% |

(Most damaging modalities, Moreno 2002)

5th Benefit: Individualised Pre-Post Training and Competition Work.

Within the pre-training and competition work in football we find the different warm-ups that provide an improvement in energy and oxygen supply, favouring muscular elasticity, and also prepares the joint capsules, ligaments and tendons. When specific quality warm-ups are carried out and directed by sports professionals, the speed of nerve conduction is increased, favouring reaction capacity and technique, psychologically preparing the athlete for sporting activity, preventing injuries, muscle strains, sprains and periostitis.

In the next post we will upload different specific works, here is a very basic one on how to work in a progressive and healthy way.

At this time prior to training we should add:

- 1-M.A.E analytical static (on the field or in the changing room).

- 2-M.A.D. global-specific dynamics (focusing on the sport).

- 3-Dynamic preventive exercises of the discipline (preparing the body for moments of stress that may occur in different situations).

- 4-Dynamic ballistic stretching (always accompanied by good body control).

- 5-Modality specific warm-up (maintaining tension and preparing for the competition by adding the ball and its moments of pause).

Within the post-training and competition work in football here we find different forms and work for a better recovery, being very varied and specific, we must observe which are most suitable for each athlete after the different recovery times, these will be broken down in the next blog seeing their virtues and contraindications, some of them being of utmost importance for all to establish recovery protocols.

They are necessary to collaborate in the elimination of the acute fatigue endured after competitive matches, and to minimise the chronic fatigue accumulated in advanced phases of the season and in periods of high competitive density. This chronic fatigue may be associated with decreases in performance with an increase in injury incidence (Dupont et al., 2015).

Therefore, it is interesting to include post-match recovery protocols including the following measures:

-Sleep and nutrition -Hydration

-Adapted recovery workouts. -Active regeneration.

Hydrotherapy -Electro-stimulation

-Cryotherapy -Pressotherapy

-Regenerative physiotherapy.

References:

Di Salvo, V., Baron, R., Gonzalez-Haro, C., Gormasz, C., Pigozzi, F., & Bachl, N. (2010). Sprinting analysis of elite soccer players during European Champions League and UEFA Cup matches. J Sports Sci, 28(14), 1489-1494.

Dupont, G., Nedelec, M., McCall, A., McCormack, D., Berthoin, S., & Wisloff, U. (2010). Effect of 2 soccer matches in a week on physical performance and injury rate. Am J Sports Med, 38(9), 1752-1758.

Dupont, G., Nedelec, M., McCall, A., Berthoin, S., & Maffuletti, N. (2015). Football recovery strategies. Practical aspects of blending science and reality. Aspetar Sport Medicine Journal. Vol 4. January.

Eirale, C., Tol, J. L., Farooq, A., Smiley, F., & Chalabi, H. (2013). Low injury rate strongly correlates with team success in Qatari professional football. Br J Sports Med, 47(12), 807-808.

Ekstrand, J., Hagglund, M., & Walden, M. (2011). Injury incidence and injury patterns in professional football: the UEFA injury study. Br J Sports Med, 45(7), 553-558.

Ekstrand, J. (2013). Keeping your top players on the pitch: the key to football medicine at a professional level. Br J Sports Med, 47, 723-724.

Fradua, L., Zubillaga, A., Caro, O., Ivan Fernandez-Garcia, A., Ruiz-Ruiz, C., & Tenga, A, (2013). Designing small-sided games for training tactical aspects in soccer: extrapolating pitch sizes from full-size professional matches. J Sports Sci, 31(6), 573-581.

Hagglund, M., Walden, M., Magnusson, H., Kristenson, K., Bengtsson, H., & Ekstrand., (2013). Injuries affect team performance negatively in professional football: an 11-year follow-up of the UEFA Champions League injury study. Br J Sports Med, 47(12), 738-742.