In high-level sport there is increasingly equal participation of women in most disciplines, however, at the scientific level most studies still use men as participants in sports performance research and there is much less evidence on women’s exercise physiology.

This is a major problem, as physiological differences between the two genders mean that the evidence is not directly interchangeable. One of the main factors is determined by sex hormone production, with men’s production being relatively stable after puberty, while adult women have cyclical changes in ovarian hormone production.

NUTRITION IN WOMEN

These dynamic changes in reproductive hormone profiles determine not only the differences in body composition between men and women (amount and distribution of body fat), but also how energy sources are utilised during training. Available research has found that women rely more than men on fat stores (adipose triglycerides and/or IMCL) to meet energy needs during exercise.

This means that during exercise women are more likely to deplete carbohydrate stores (liver and/or muscle glycogen). It is important to note that the depletion of glycogen stores is related to fatigue. So, from a performance perspective, the slower depletion of glycogen stores by women during exercise translates into women being more resistant to fatigue and more able to maintain performance during longer duration events.

INFLUENCE OF THE MENSTRUAL CYCLE ON SPORTS PRACTICE

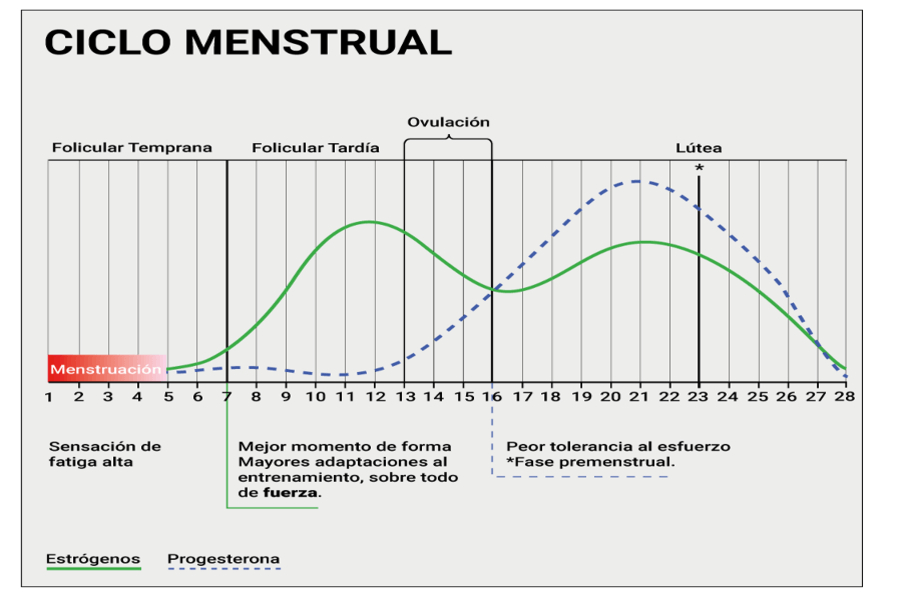

Research has shown that fuel storage and utilisation during exercise is primarily mediated by oestrogens. It has also been found that oestrogens have an anabolic effect on skeletal muscle while progesterone has the opposite effect. We know that menstruation consists of 4 phases and that in each of these phases there is a fluctuation in hormone production, of which the following are the most important:

- Menstrual Phase

- Follicular Phase (low estrogen and progesterone levels)

- Ovulation Phase (high oestrogen levels, reduced progesterone)

- Luteal Phase (high oestrogen and progesterone)

As can be observed in the late follicular phase and in the ovulatory phase, the highest levels of oestrogens are present, which suggests that during this period there is less fatigue in training, taking into consideration that there is a greater dependence on fats as a source of energy.

Conversely, it has been reported that performance may be slightly reduced during the early follicular phase where oestrogen levels are lower.

Despite the above, there is insufficient evidence at this time to suggest that nutritional recommendations should change at different phases of the menstrual cycle.

DIETARY STRATEGIES FOR THE FEMALE ATHLETE

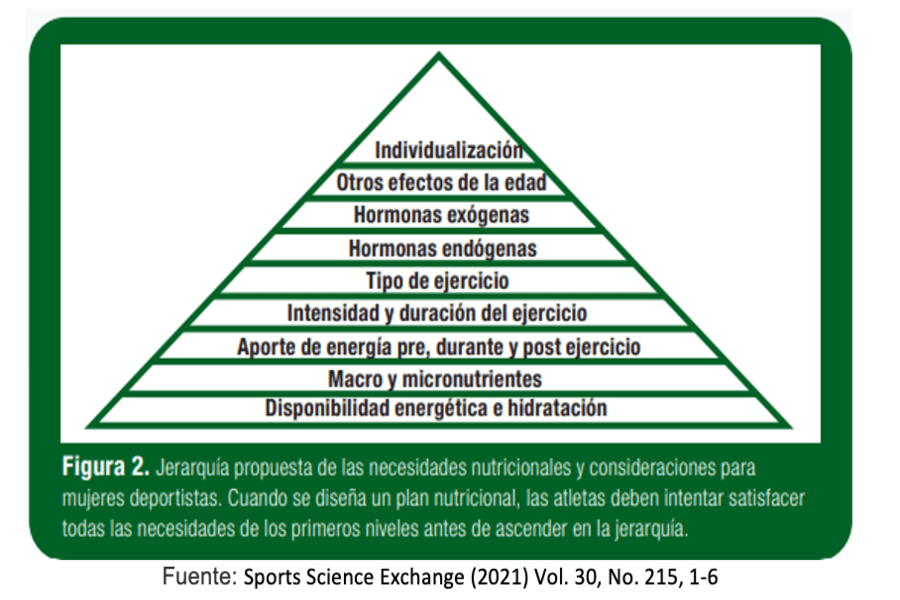

The journal Sports Science Exchange (2021) recommends establishing a hierarchy of nutritional needs to advise female athletes, where they are encouraged to focus on building a strong nutritional foundation before in-depth personalisation.

The base of the pyramid is energy availability, as one of the main nutritional problems detected in female athletes is obtaining adequate energy to meet the demands of sport and daily life activities.

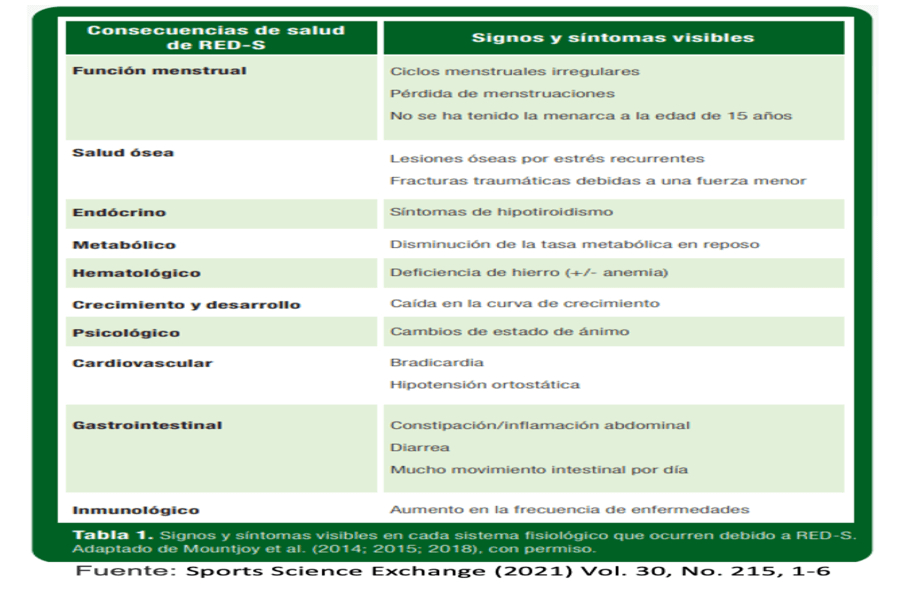

Low energy availability manifests itself through a constellation of symptoms that affect health and sporting performance. This set of symptoms has been termed “Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S)”, which are detailed in the following table:

In addition to considering this adequate energy intake, it is necessary to ensure macro- and micronutrient requirements. Available studies have not found a significant influence of the menstrual cycle to generate specific nutritional recommendations, however, it is recommended to monitor protein intake during the luteal phase (from day 15 to 28), as increased progesterone levels lead to higher rates of protein catabolism.

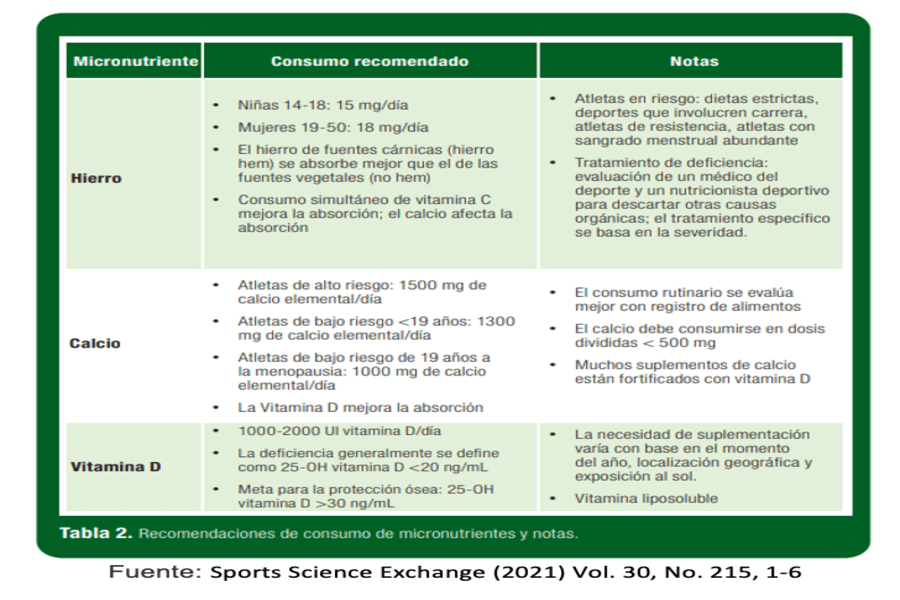

In terms of micronutrients, female athletes are known to be particularly prone to iron, calcium and vitamin D deficiencies. The following table shows the recommended intake:

To identify the risk of deficiency, it is advisable to assess with a sports nutritionist the consumption of the main food sources of these micronutrients to ensure an adequate intake.

CONCLUSION

- The available studies do not represent significant evidence to generate special nutritional recommendations for each phase of the menstrual cycle.

- Female athletes should first be concerned with maintaining adequate energy availability to meet caloric requirements, as a relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S) generates a constellation of symptoms that negatively impact health and athletic performance.

- As female athletes are at increased risk of micronutrient deficiencies, it is essential that they receive information from a specialist to ensure adequate calcium, iron and vitamin D intake.

- There is a lack of research, and it is necessary to have recommendations adapted not only to the physiological characteristics of women but also to the demands generated by each sporting discipline.