Undoubtedly, training methodology in any sport has undergone many changes over the years.In football, the concept of “periodisation” marked a turning point in training planning.

The development that this concept has undergone goes from the traditional periodisation, where training was based on analytical exercises and it was believed that these results would later be combined in competition, to Tactical Periodisation.

Born only forty years ago, it focuses all its training concerns on assimilating and understanding the Game Model composed of principles and sub-principles, which will be proposed in the competition, eliminating the most conventional beliefs of the previous theories of sports training. In addition, it includes several branches of knowledge such as neurobiology, which is new in this sport and fundamental in the creation of player’s habits.

Tactical periodisation

Tactical periodisation is a training methodology that emerged more than forty years ago from the hands of Víctor Frade, who, based on his experiences, began to question the training methodologies that had existed up to that time.

What is tactical periodisation?

It is a training methodology whose maximum concern is the “playing” that a team intends to produce in competition through its game model. This model is transmitted to the players through a pedagogical process, where there is no room for decontextualised and analytical elements, given the globality and unpredictability of this non-linear state sport (Tamarit, 2007).

Delgado Bordonau and Méndez Villanueva (2012) indicate that the priority objective of tactical periodisation is to ensure that the “game” that the team develops must be previously trained and learned respecting the parameters of the internal logic of football.

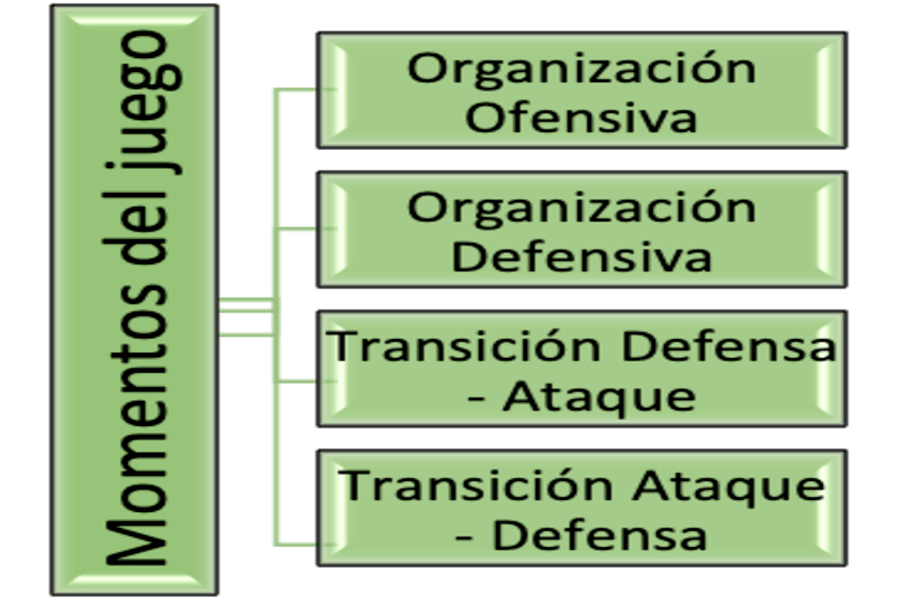

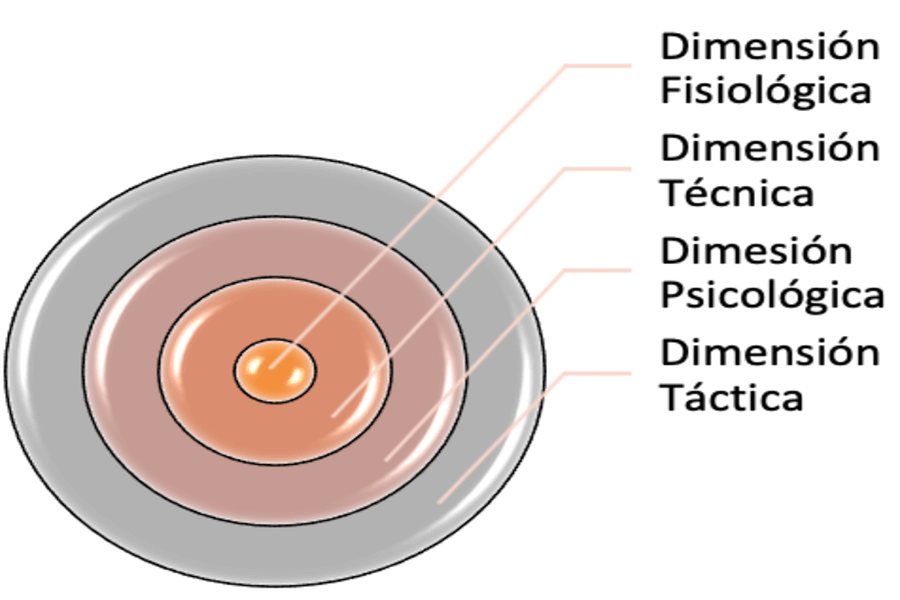

As we can see in Figure 1, each game action requires attention to the four existing moments (defensive organisation, offensive organisation, defence-attack transition, attack-defence transition) and in turn also requires a decision (tactical dimension), a motor action (technical dimension), a specific movement (physiological dimension) and control of the will and emotional state (psychological dimension).

Figure 1. Moments of the game and Dimensions of Tactical Periodisation.

In short, as the main objective of this methodology is the “playing” of the team, the game model should be the guide for this whole process, in order to achieve a specific adaptation, always respecting the methodological principles that support it.

Game model, script of the teaching process

The concept of playing model is often confused with the system of play that is used in terms of player positioning or with the idea of the game as such that is transmitted by the coach or the team. The model of play is based on the players’ behaviour and relationship with each other to express their way of understanding football (Tamarit, 2007).

The typology of the “game” of a football team is obtained through a series of regularities created by the experiences and acquisition of this “playing”, where training is the main tool to reach the assimilation of how you want to play (Reis, 2018).

The team’s attentional focus on how to play in competition is based on the behaviours and interaction of the players and it is these who form the structure that make up the game model, which must be flexible and modifiable to adapt to the requirements of the competition. The fundamental elements of a game model will be those that give it its previous shape, as we can see in Figure 2 (Tamarit, 2007).

Figure 2. Influential elements in the development of the Game Model. Adapted from Tamarit (2007).

Learning process of a football game model

The learning process of a game model will always be subject to the principles, sub-principles and sub-sub-principles proposed by the coach. They are the ones that will allow us to acquire a “game” identity. These elements will be subject to the prior intention, which is not the same as the idea of the game.

The prior intention is the “play” that is intended to be developed in each of the moments that occur in the “game” and the idea of the game is the type of football that the coach has in mind and would like his team to play (Tamarit, 2013).

Within the idea of the game, one of the most transcendental elements when elaborating the “previous intention” is to indicate how the team should behave in each of the phases of the game (with the ball, without the ball, after recovering it, after losing it).

This is why all team members must be aware of what they have to do at each moment of the match, generating certain behaviours and patterns of play in different contexts that are manifested in the competition. These patterns and behaviours will express a common collective dynamic behaviour, characterising a certain game identity, which can be called functional organisation (Delgado Bordonau and Méndez Villanueva, 2012).

Patterns of the game model

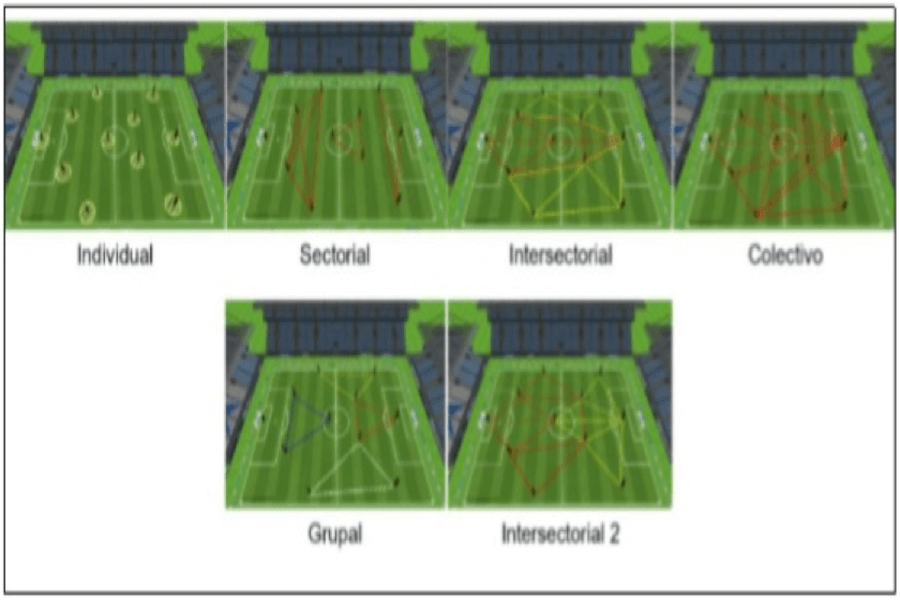

The patterns that will shape the pattern of play in tactical periodisation are as follows:

- Principles of the game: Response patterns in relation to the collective actions of the team.

- Sub-principles of the game: Response patterns in relation to sectoral, intersectoral or group actions.

- Sub-sub-principles of the game: Response patterns in relation to individual team actions.

Figure 3 shows the levels of structural organisation and we can see the relationship of the actions on the football field.

Bordonau and Méndez Villanueva (2018).

According to Oliveira (2004), the relationship between the principles, sub-principles and sub-sub-principles constitute the game model, thus expressing a functional organisation that provides the team with its own identity. Therefore, for there to be an organisation of the previous intention, it is necessary to clearly establish everything that is intended to be carried out in each of the phases of the game, adopting a series of coordinated actions (Delgado Bordonau and Méndez Villanueva, 2012).

Putting periodisation into practice in training

Once a part of the previous intention has been developed, assessing all the factors involved in it in order to obtain regular behaviour in the team, we will operationalise it through the implementation carried out in training.

The coach will proceed to execute an idea of “play”, but he cannot limit himself to thinking only about it, but he must also transmit it clearly and concisely so that the players can assimilate the “football” that he wants to give shape to in the team.

Throughout this complex process, it will not be enough just to transmit the necessary information, but to allow the creativity and imagination of the player by being flexible with them and at the same time imposing disciplines to achieve the objectives set.

It is very important that the players understand what they must do at each moment of the game, taking into account the previous intention and the principles/sub-principles/sub-sub-sub-principles that involve them.

Therefore, the greater the elaboration of the game model, the greater the degree of understanding that will be obtained in the resolution of situations, without becoming a mechanism and thus allowing the player to express his creativity.

The coach’s intention must be that the players understand what the collective way of playing (game idea) is and for this it is essential to have a specific “prior intention” that is clarified from the beginning, based on the principles, sub-principles and sub-sub-principles that are identified with a certain style of play (Tamarit, 2007).

According to Reis (2018), we will reach the “prior intention” as a result of the connection between the contextualised conditions of the club/team and the coach’s idea of the game.

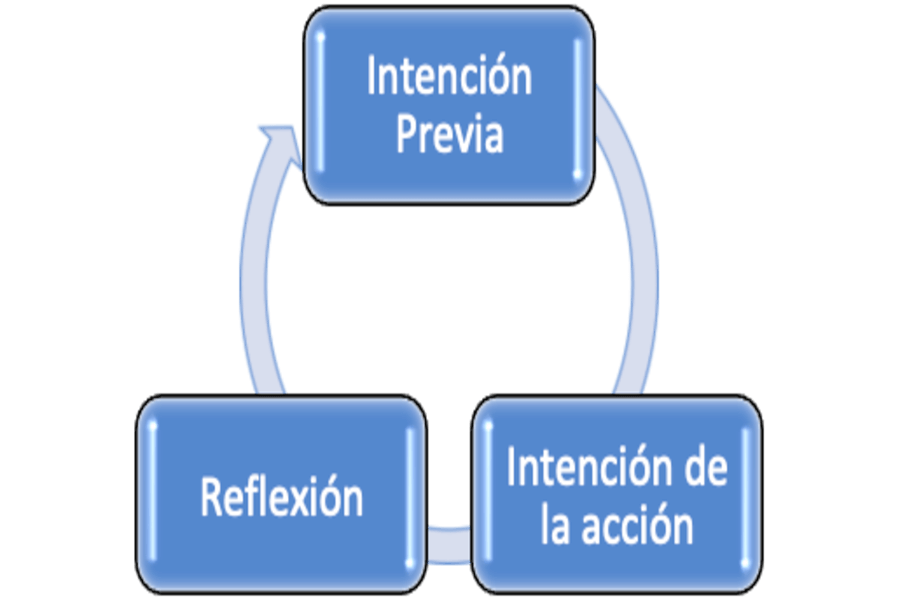

Tamarit (2007) states that through the tasks in training and with this prior intention already operationalised and concretised, situations different to those expected will arise through the players’ interaction with each other, based on the characteristics of each player and their contextualised adaptation, forming a new structure that will be called “Intention in action”.

Both structures will stimulate a process of constant interaction, provoking a game model in continuous evolution, despite maintaining a solid base.

This interaction will allow us to reflect on the individual characteristics of the players together with the situations that are generated through the relationship between them in the collective actions, thus being able to discard or incorporate desired behaviours in the previous intention, creating a new structure called “Reflection”, thus completing the “Game Model Loop” (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Game Model creation process. Adapted from Tamarit (2007)

This is why the existence of an adopted game model is denied, but the created one is, because when moderating and operationalising with it, things happen that the coach was previously unaware of and they become part of the model.

It will be obvious that as days, training sessions and matches go by, we will gain new experiences that will constantly modify the game model (Tamarit, 2007; Reis, 2018).

Organisation of training sessions on the basis of the model

In order to achieve an adequate operationalisation of the model, the training sessions should focus on the player, not individually, but as part of the team.

The role that the player assumes within the team is very important, as it will entail an individualised process where he will be able to offer the coach his understanding and idea of football, which will be of vital importance for the development of the model. The coach must know the capabilities and characteristics of his players together with the way of understanding football for them and with all this information create a certain style of play.

Therefore, the coach must constantly pay attention to the context and everything that surrounds him, as well as his players, in order to best manage the operationalisation of the game model (Delgado Bordonau and Méndez Villanueva, 2012).

The main intention of the coach must be that all the players in the team possess the same collective idea of the game, both consciously and subconsciously, which will not be easy as each player, due to the culture they come from and all the formative experience they have received, will have a specific understanding of the “game”.

Therefore, we must eliminate the usual response pattern of the players and design a common one, creating habits of intention that will establish principles and subprinciples, as specific response patterns in accordance with our game model. These habits and patterns are obtained through the experience lived in training, provoked by the coach (Tamarit, 2013).