When we talk about soccer we are referring to the”king of sports” being played by children, teenagers and adults of either sex. Obviously, the levels at which the game is played are very varied: from kickabout between friends to international competitions involving elite athletes, so it will be difficult to generalize with the recommendations that can be drawn from this article and nutrition for soccer players. In addition, we all have in mind the physical differences between Neuer (Bayer Munich goalkeeper) and Jordi Alba (FC Barcelona Lateral), which makes it difficult to group all the recommendations into one. We must even differentiate according to the time of the season (Holway & Spriet, 2011).

The differences can also be wide within the same group of players. For example, there may be a midfielder who has covered 12 km on average, almost a third of which has been at high intensity, while his team-mate may have total marks of 10 km with 2 km at high intensity.

In general, we will try to refer to nutrition for players who play at least one match a week and have at least two training sessions (training sessions such as those at the FC Porto Dragon Force school within the Soccer Interaction academy), so this text may be useful for those who compete in lower divisions even for fathers and mothers.

As we know, football is a highly intermittent sport with high intensity racing and very specific actions that demands a great capacity for resistance. Maximum effort actions are alternated with periods of jogging or walking in which active or passive recovery takes place. In this way it is clear that different metabolic pathways are involved in obtaining energy (Williams & Rollo, 2015).

More or less, on average, during the 90 minutes of the match, the field players (all but the goalkeeper):

- They cover a total of 9 – 13 km on average.

- They perform a total of approximately 1350 game actions (including direction changes every 4 – 6 seconds).

- They run about 220 races at high speed, reaching speeds of around 32 km/h.

- On average, approximately 1100 kcal are spent.

Obviously, in matches where extra time is required and the time increases to 120 minutes, all these numbers will be increased.

All these efforts will lead to partial (or total) depletion of glycogen stores, dehydration and hyperthermia, which may be related to fatigue. In fact, it has been observed that the number of sprints, high intensity races and distance covered are less in the second half and especially in the last 15 minutes, something perfectly logical.

The search for strategies aimed at reducing this fatigue will be the key to trying to make a difference with the opponent and achieving victory.

Not only will metabolic factors or energy requirements be important when structuring the diet before a match, but the location of the match, the time available for meals and the players’ own tastes will be essential.

If we talk about star’ nutrients in terms of fuel for football it would be carbohydrates.

Carbohydrates, are the sugars, starches, and fibers found in a wide variety of foods such as fruits, grains, vegetables, and dairy products. They are called carbohydrates, because they contain carbon, hydrogen and oxygen chemically.

Carbohydrates are one of the basic food groups and are important for healthy living. They are macronutrients, which means that they are one of the three main forms of substances that the human body uses for energy or calories. All macronutrients must be obtained from the diet; the body cannot produce them on its own.

Carbohydrates provide the body with glucose, which is converted into energy, which in turn is used to maintain body functions and physical activity.

The healthiest sources of carbohydrates are the unprocessed or minimally processed ones such as whole grains, vegetables, fruits, and grains.

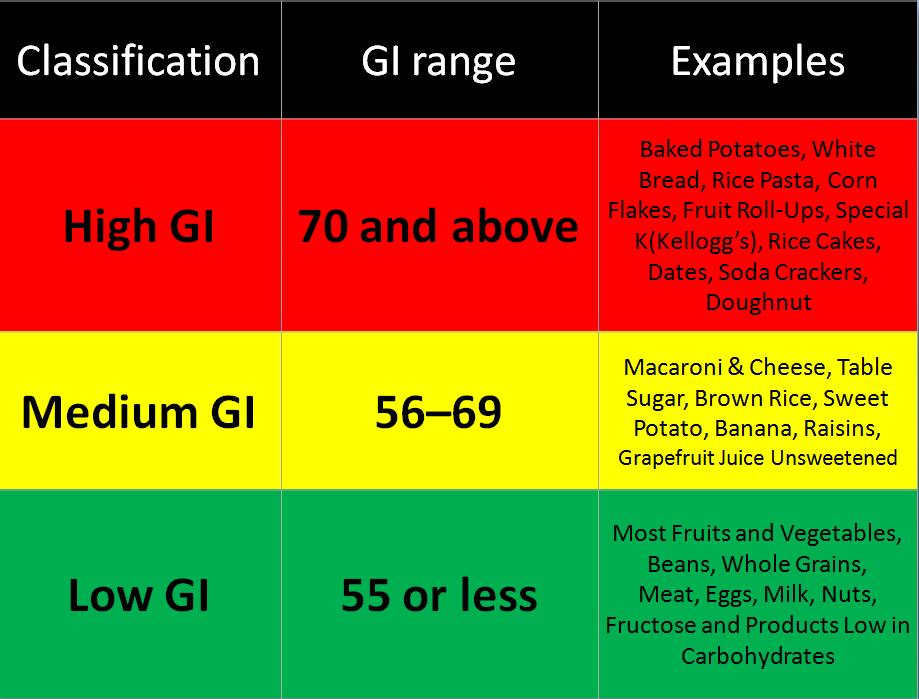

Less healthy sources include white bread, cakes, sweetened soft drinks and other highly processed or refined foods. So we can distinguish according to the”rise in blood glucose” between:

Knowing this we must reach a compromise between consuming sufficient quantities and avoiding gastrointestinal problems during the encounter that could arise as a result of excessive intakes.

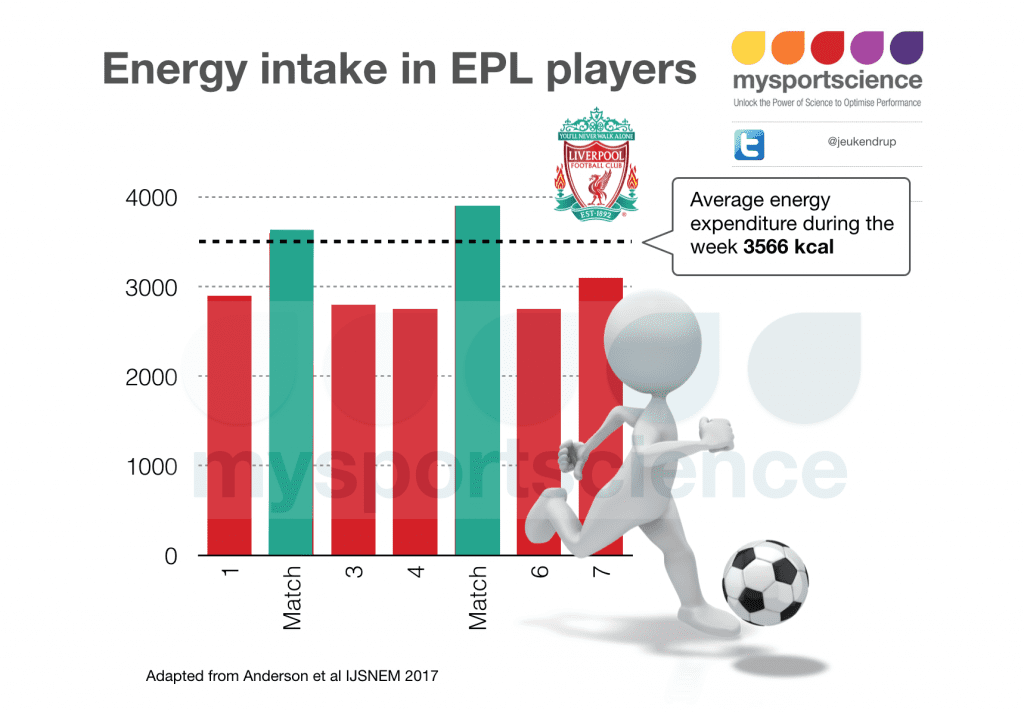

Something that has been observed in studies of top-level players, such as this one by Lian Anderson, is that, although the energy and carbohydrate requirements are higher on match days, due to the stress generated by the match or the possible trip that players may have to make, the eating pattern is altered, making it difficult to adapt to the requirements (Holway & Spriet, 2011; Anderson L et al, 2017).

Graphic 1: Taken from Jeukendrup A.

Although, as in almost every field of nutrition, there are both pros and cons, the evidence strongly suggests that eating a high-carbohydrate meal before exercise is beneficial for performance. Something that may surprise many people is that many studies are in favour of the fact that the carbohydrates that must be consumed before exercising should be low glycaemic index, since it has been seen that this type of carbohydrate maintains constant blood glucose levels for longer than those of high glycaemic index, also favouring the greater use of fats as fuel and exerting a protective effect on glycogen reserves and delaying the appearance of fatigue. Another point in favor of low glycemic index carbohydrates as a pre-exercise meal is that they seem to prevent the sensation of hunger from appearing.

In view of these results, it seems appropriate to choose foods that provide low glycemic index carbohydrates, which should be consumed in the 2 – 4 hours prior to the match. However, as we said at the beginning, in football, not only is an energy route used to satisfy the demands of play or training, but in explosive efforts they require the degradation of glycogen (carbohydrate deposits in the muscle and liver) and phosphocreatine for the rapid production of ATP (energy). This is very important because it is known that the use of fats as the main fuel, in this case derived from the consumption of low glycemic index carbohydrates, is not capable of providing energy fast enough for the demands of high intensity exercise (Williams & Rollo, 2015).

Undoubtedly, achieving a balance between high and low glycemic carbohydrates will be vital to achieve:

- Start with glycogen deposits at maximum.

- Maintain adequate blood glucose levels throughout the match.

- Avoid the appearance of fatigue at the end of the meeting.

- Reach the recommended amounts of carbohydrates without causing discomfort.

In order to achieve this, the recovery strategy after each match and training sessions will be very important, as we will see later on, especially when there is little time (2 – 3 days) between matches.

As a general recommendation, we could say that the type of carbohydrate (low or high glycemic index) will depend on how the athlete’s glycogen reserves are (Holway & Spriet, 2011; Williams & Serratosa, 2006). That is, if the recommended amounts of carbohydrates have not been consumed after the previous match or after a series of intense training sessions to ensure the replenishment of the reservoirs, it is possible that high glycaemic carbohydrates may need to be emphasized in the pre-game meal.

It has been observed that, although the time between meals is insufficient (<3 hours between meals) to regenerate the liver and muscle stores, an increase in reserves of between 11-15% can be achieved by ingesting carbohydrates with a high glycaemic index, something that does not happen after the consumption of an equivalent amount of carbohydrates with a low glycaemic index (Williams & Rollo, 2015). On the other hand, if post-match/post-training recovery has been adequate, moderate-low glycemic index carbohydrates placed as pre-part meal may be a very good option given the benefits described above:

A FUNDAMENTAL QUESTION MUST BE ASKED BY THE ATHLETE: WHAT SHOULD I AND SHOULD I NOT EAT?

- 4 hours before training: The meal should contain carbohydrates + protein and very little fat, e.g. pasta or rice with chicken breast and steamed vegetables.

- 3 hours before training: The meal should contain carbohydrates + protein, e.g.: hot-cakes with honey and turkey breast + 1 cup of light milk.

- 2 hours before training: The meal should contain carbohydrates + low protein, e.g. turkey breast sandwich, fruit with light yogurt and granola or oatmeal.

- 1 hour before training: Meal should contain carbohydrates, e.g. low-fat cereal bar, jam sandwich, fruit with oats and honey.

- To avoid: fats, fibre, irritants and foods that are difficult to digest ,fried or breaded foods and whole grains, sauces, spices or seasonings.

Another of the problems that a footballer faces in each match is a decrease in energy due to a reduction in glycogen reserves, which leads to a decrease in the number of meters travelled, in the intensity and in the slowing down of decision making. That is why it is important to take hydrates during the game such as isotonics, gels, gummy jellies, etc. using breaks in the game and rest as key times to introduce them (Holway & Spriet, 2011).

Based on the existing evidence, we can say that the consumption of carbohydrate enriched drinks (concentration of 6%, i.e. 6g of sugars per 100ml) together with electrolytes during the match offers clear advantages over water intake, such as improved sprint speed, motor skills and even mood in the final minutes. These positive effects have also been observed when the subjects started with good pre-exercise glycogen levels (Williams & Rollo, 2015).

With the number of times we’ve mentioned glycogen in this article, you’re sure to be able to guess where the recovery strategy is going. Indeed, trying to regenerate these valuable reserves of muscular and hepatic glycogen so that they are full in the next match, although it will also be very important to accelerate the repair of muscle damage produced in the match and the rehydration of the footballer. This is especially important when matches are played within days (Ranchordas et al., 2017).

This is important as there is a higher recovery rate of glycogen in the first 2 hours after exercise, so delaying carbohydrate and fluid intake beyond this range can compromise the restoration of deposits. This is why footballers should be encouraged to consume replacement drinks or snacks as soon as possible after the final whistle (Williams & Rollo, 2015).

The general recommendation for carbohydrate intake within the first 4 hours after the match is between 1 – 1.5 g/kg weight/hour, preferably taken frequently (every 30 minutes) rather than over longer periods of time and with a high glycaemic index. Similarly, the addition of 0.2 – 0.5 g/kg

protein weight to carbohydrates may improve glycogen resynthesis and improve the repair of muscle damage (Ranchordas et al., 2017). In general terms for a 60kg person this should take about 60g-90g of hydrates and about 18-30g of protein.

Food options for the supply of 50g of carbohydrates for quick absorption. Extracted, translated and modified from Ranchordas et al., 2017.

•

- 250-350 ml milk shake or fruit smoothle

- 2 slices of bread/toast with jam, banana or honey.

- 2 cereal bars

- 300g of stuffed baked potato

- 2 gels carbohydrates – 2 gels

- 700 -800 ml of sports drink

- Fruit Macedonia with 200g of yoghurt

- Sandwich with meat filling

- Sports bar

- Rice cakes – Rice cakes

- Stuffed wrap-type pancakes

- Medium bowl of popcorn

- Medium bowl of sweet potato

- Medium sized pizza with a thin base

- Panini

Easily digestible food options that provide 10g of protein for the immediate recovery phase. Extracted, translated and modified from Ranchordas et al., 2017.

• 300 ml de leche o batido lácteo

• 20-30g de barrita deportiva enriquecida en proteínas

• 10-15g de proteína whey en polvo

• 200g de yogur griego

• 250g de flan bajo en grasa

- 300 ml milk or milk shake

- 20-30g protein enriched sports bar

- 10-15g whey protein powder

- 200g Greek yoghurt

- 250g low-fat flan

An important aspect is to avoid gastrointestinal discomfort due to large intakes of carbohydrates, something for which carbohydrate mixtures of multiple transporters (glucose : fructose, maltodextrins : fructose, etc.) are very useful, as we saw in the article on gastrointestinal discomfort.

Beyond the post-match period, the carbohydrate recommendation for the overall day in weeks of maximum match demand (2-3 matches/week) is 6 – 10 g/kg weight/day, which is recommended to be consumed in 3 – 4 main meals supplemented with frequent snacks.

The truth is that unlike carbohydrates, there is little written about the fat and protein requirements for football players. However, some authors (Ranchordas et al., 2017) recommend protein intakes between 1.5 – 2 g/kg weight per day, while fat would represent the remaining energy until the requirements are met. In addition, they recommend distributing these proteins in several doses (about 6 x 20 – 25g of protein; total 120 – 150g protein/day) every 3 hours.

As for the post-partum, these same authors speak of the fact that introducing a small amount of protein (40g is enough) is beneficial for maximizing muscle protein synthesis and mitigating muscle damage. If you look, a protein intake of 35 – 40g of protein in a player of 75 kg would be about 0.5g/kg of weight approximately, so it would meet the recommendation to enhance glycogen recharge.

On the other hand, it is difficult to find concrete recommendations on the amount of fat to be consumed by these athletes, since they simply represent the remaining energy of the carbohydrates and protein intake. If we look at a collection of articles collected by Holway & Spriet in 2011, in which the dietary intakes of more than 300 professional and semi-professional footballers were collected, we see that the daily percentage of energy corresponding to fat is, in the vast majority of cases, between 25 – 35%.

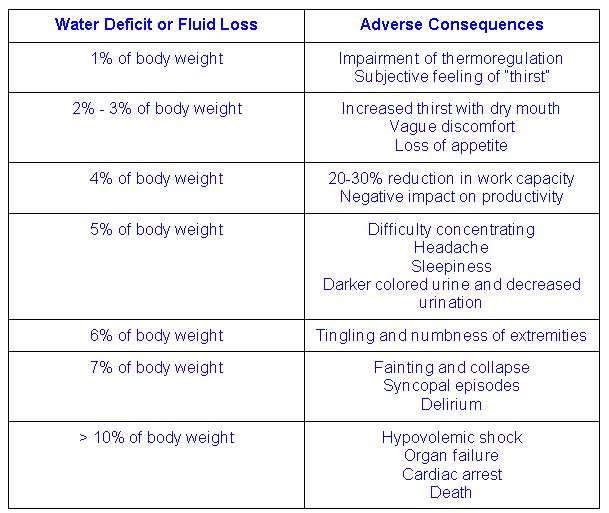

As in many other sports, footballers have repeatedly been found to have some degree of dehydration even before the start of a match or training session (Holway & Spriet, 2011; Maughan et al., 2007). Given the clear relationship between dehydration and factors such as fatigue or cramping, controlling fluid intake will be as important or even more than adjusting macronutrients.

I

Image 1. Consequences of dehydration in football players.

In addition to water loss, one of the main causes of muscle cramps and spasms is the loss of sodium through sweating. This will depend a lot on the sweat rate and the salt loss of each player, which can vary between less than 1 g and more than 10 g. In cases where there are large sweat losses, drinks providing between 20 – 25 mmol/L of sodium can be really useful (Maughan et al., 2007).

It has been observed that the consumption of about 600 ml of water or sports drink 30-45 minutes in advance leads the athlete to a good state of hydration (Holway & Spriet, 2011).

Other factors that will affect the hydration status of the athlete are the stress of the day of the match, which can alter the usual patterns of fluid intake, and that the match is played in hot climates with high humidity.

A simple strategy to try to control the hydration level during the match is to ensure that approximately half a litre of sports drink is consumed during the break.

If you want to know what to eat before a soccer game, click

During the post-match recovery, rehydration is especially important, especially if the next match is to be played in a few days or if we are talking about days with a double training session. Evidently, the composition of the drink used will influence the rehydration capacity, with the recommendation (Heaton et al., 2017) being to consume between 1 – 1.5 L of drink per kg of weight lost, containing 20 – 50 mmol/L (Heaton et al., 2017; Ranchordas et al., 2017) and 6 – 12% of carbohydrates.

Sodium, in addition to being the main electrolyte lost through sweating, improves the palatability of the drink and stimulates the desire to drink, which, together with its ability to promote fluid retention, make it an indispensable element of replacement drinks.

With regard to carbohydrates, we must bear in mind that the most concentrated drinks (10 – 12% carbohydrates) are more susceptible to generating gastrointestinal discomfort, something that can be solved, for example, by combining carbohydrates from multiple transporters, as we have already mentioned, by introducing high molecular weight carbohydrates or simply by consuming drinks with more moderate concentrations and that have been tested previously.

Water as such is not a good make-up drink as it lacks electrolytes and carbohydrates.

As mentioned above, the intake of liquids and carbohydrates can be done in different ways: with sports drinks, with gels and water or with natural fruits.

Correct hydration with electrolytes during the match will help to prevent muscle cramps and prevent the player’s performance from diminishing during the match. It is difficult to predict hydration losses as they are closely linked to the ambient temperature and to each player. Players must learn to know their usual level of perspiration to ensure proper hydration.

- Sports drinks provide energy, electrolytes and hydration. It is recommended for use in both training sessions and prolonged competitions.

- Gels are a convenient and quick way to eat carbohydrates and should be accompanied by water as a source of hydration.

- The bars provide carbohydrates, proteins, vitamins and minerals. It’s an easy way to make intakes before the game or after the game. They do very well during endurance training programs.

- Shakes mainly provide carbohydrates and proteins. In low volume they provide a large amount of energy. They are a quick solution for making a recovery intake after physical activity or before resistance training. It is well tolerated by the stomach and is used by many sportsmen and women who have gastrointestinal problems as a result of eating solid food before the match.

- Vitamin and mineral supplements are indicated when travel makes it impossible to count on an adequate supply of food.

There are very few studies that have directly demonstrated (due to the lack of studies and the difficulty of conducting them in football) the benefits of nutritional supplements on football performance. Creatine is one of the most widely used supplements, as there is evidence of the benefits of creatine loading on performance in episodes of repeated high intensity physical activity with a short recovery period. The indicated dose of creatine loading is between 20-30g per day spread over several intakes over 5 days. The proper amount for maintenance decreases to 2-5g/day. Creatine intake should be made in conjunction with carbohydrate foods to improve response. It should be noted that the creatine load produces a weight gain of about 1kg, supposedly of fluid retention.

Caffeine can improve the performance of prolonged exercise by reducing the perception of fatigue. A dose of 20mg of caffeine per kg body weight is enough to be effective. It should be taken just prior to the onset of fatigue.

With everything explained here, below you can see a menu of a professional team as an example.

- Breakfast: Cereals or bread ,Milk and coffe , Fruit.

- After training: Proteins and carbohydrates milkshake, Fruit.

- Lunch: 1st dish: rice, pasta, legumes or potatoes. 2nd dish: meat, eggs or fish (blue or white) Vegetables garnish Dessert: Fruit or yogurt

- Snack: Fruit, milk, yogurt, dried fruit or sandwich.

- Dinner: Carbohydrates (just a few) Vegetables Dessert: Fruit and dairies

Miquel Pérez Martí.

Dietista- Nutricionista. Col CV00849.

F C Porto- DF Valencia-Enguera

References

- Bangsbo J., Mohr M., Krustrup P. (2006). Physical and metabolic demandas of training and match-play in the elite football player. Journal of Sports Sciences.

- Heaton L. E. et al., (2017). Selected In-Season Nutritional Strategies to Enhance Recovery for Team Sport Athletes: A Practical Overview. Sports Med.

- Holway F.E., & Spriet L.L. (2011). Sport-specific nutrition: Practical strategies for team sports. Journal of Sports Sciences.

Maughan R.J. & Shirrefs S.M. (2007). Nutrition for Soccer Players. Current Sports Medicine Reports. - Nédélec M. et al., (2012). Recovery in Soccer. Part I: Post-Match Fatigue and Time Course of Recovery. Sports Med.

- Ranchordas M. K., Dawson J. T., Russel M. (2017). Practical nutritional recovery strategies for elite soccer players when limited time separates repeated matches. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition.

- Russel M. & Kingsley M. (2014). The Efficacy of Acute Nutritional Interventions on Soccer Skill Performance. Sports Med.

Williams C. & Rollo I. (2015). Carbohydrate Nutrition and Team Sport Performance. Sports Med. - Williams C. & Serratosa L. (2006). Nutrition on match day. Journal of Sports Sciences.

- Liam Anderson, Patrick Orme, Robert J Naughton, Graeme L Close, Jordan Milsom, David Rydings, Andy O’Boyle, Rocco Di Michele, Julien Louis, Catherine Hambley, John Roger Speakman, Ryland Morgans, Barry Drust and James P Morton Energy Intake and Expenditure of Professional Soccer Players of the English Premier League: Evidence of Carbohydrate Periodization. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism. Ahead of Print 2017.